Table of Contents

- 1. Veronica, The Patron Saint of Photography

- 2. Space, Time, and the Projective Image

- 3. The Livestream as Portal

2. Space, Time, and the Projective Image

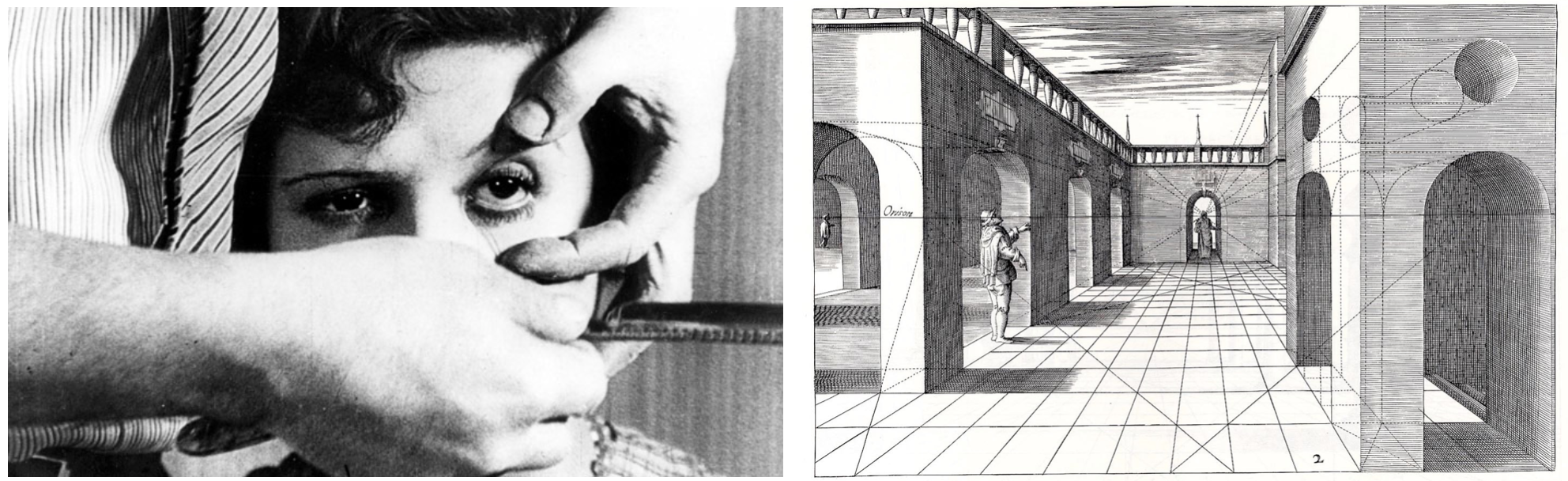

Consider, if you will, the two images above. They serve to contrast two different ways we might think and talk about space itself. On the left, we encounter a meaningful distribution of things, including a straight-edged razor, in space. It is particularly meaningful, one might guess, for the woman whose eyeball is threatened. This might serve as a reminder that we all encounter space from an embodied centre, such that events (razors, wasps) close to our face, or even near our body, necessarily matter more than razors and wasps on the other side of the planet. This is space as encountered by a subject, for whom things matter.

We might contrast that with space as illustrated in the drawing on the right, which employs the technique of linear perspective. This technique was developed in the 15th Century in Italy, and it served to make depth in paintings and drawing intelligible in a very important fashion. Formally, it uses geometric projection, calculated on the basis of a single static viewing point, with some further complexity introduced if the scene depicted contains planar surfaces that are not perpendicular to the viewing axis. The mathematical details need not trouble us much. Suffice it to note that this technique accurately captures a great deal of projective detail that provides depth cues, such that the space revealed in this fashion is perfectly intelligible—intelligible, and uncharged. In this representation of space, no point is privileged, and our measurement practices are very well developed, allowing us to posit equivalence between a metre here, in the room we sit in, and a metre, say, on the moon. This is, of course, an "objective" way to regard space, but the term "objective" here needs to be interpreted carefully, if we are to allow a "subject" also to enjoy some claim to reality.

Two characteristics of an old view of the nature of reality interest us here:

- 1. Reality is material, and thus volumetric, and

- 2. Mind is separate from matter.

These two linked views have their origin in the birth of modern science, around the 16th and 17th Centuries. In this period, the best informed views of how stuff is distributed in space underwent a very significant change. The cosmos had previously been understood as centered at the Earth, and split up into different realms, each inhabited by different kinds of objects and beings, and subject to different kinds of order. The altered picture that arose with Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton displaced the Earth, and made volumetric space into a uniform container, in which matter was moved mechanically. Mechanical motion, as described with astounding success by Newton in his famous three laws, is lawful, and deterministic. This gave rise to a view of a mind-independent material world in which everything from the motion of the planets to the scurrying of ants unfolded like clockwork. There is no place for a freely acting agent in such a view, and the understanding at the time of Newton and Descartes was that animal and plant activity was mechanical in this strict sense. From ape to worm, all animals were understood to be machines. The only free agents recognised in this worldview, which was still completely beholden to a Christian theology, were people. We humans alone of all created beings were endowed with souls and free will, making our actions unpredictable, while those of the donkey, the fish and the earthworm lacked true agency, free will, and thus spontaneity.

To this cosmological picture, René Descartes added the notion that matter (res extensa) and mind (res cogitans) were two entirely different domains, a position known as substance dualism. This convenient fiction allowed one to think of a material reality, distributed within the three dimensions of extended space, and simultaneously to allow for the qualitative reality that is the stuff of lived experience. It separated, by fiat, the reality of the subject from that which is observed, creating both a framework within which a disinterested science could make enormous progress, and an explanatory challenge as it interposed a chasm between the inert world so described and the experience of any living subject.

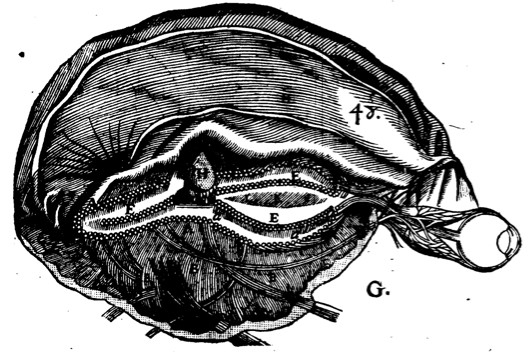

Fig. 8: The

centrally located pineal gland, labelled "H", as mis-located by

Descartes (1664). (Image credit).

Descartes' metaphysics are not to anyone's taste today. In order

to shore up this remarkable dualism that apportioned the

qualitative world of reality as experienced to one domain, and the

quantitative world of observation and measurement to another, he

had to introduce a means for these two to interact. Interaction is

necessary if goings on in one such domain (the subjective, in

which I decide, plan, intend, and will, apportioned to the soul)

are to influence goings on in the other (the objective, in which

all motion is mechanical, including the body). Before Descartes,

the scholastic tradition had understood the soul and the body to

be more intimately intertwined, such that the soul was involved in

much of what we would now consider to be physiology: respiration,

digestion, etc. By Descartes' time, a growing confidence in the

explanatory power of mechanistic notions allowed him to apportion

even these functions to the machine-like body, effecting a radical

split between the intellect and the gross material world of the

flesh. In his account, Descartes helped himself to a little

understood gland hanging from the base of the brain, the pineal,

whose role in the body was not understood at that time. The

pineal, which lies on the mid-line of the head, between the third

and fourth ventricles, appealed partly because it was a singular

entity, and not doubled on the right and left, as are all brain

structures. In somewhat convoluted fashion, Descartes appealed to

this structure to underwrite the interaction of the soul and body,

an attempt that he never completed to either his satisfaction or

that of others.

Fig. 8: The

centrally located pineal gland, labelled "H", as mis-located by

Descartes (1664). (Image credit).

Descartes' metaphysics are not to anyone's taste today. In order

to shore up this remarkable dualism that apportioned the

qualitative world of reality as experienced to one domain, and the

quantitative world of observation and measurement to another, he

had to introduce a means for these two to interact. Interaction is

necessary if goings on in one such domain (the subjective, in

which I decide, plan, intend, and will, apportioned to the soul)

are to influence goings on in the other (the objective, in which

all motion is mechanical, including the body). Before Descartes,

the scholastic tradition had understood the soul and the body to

be more intimately intertwined, such that the soul was involved in

much of what we would now consider to be physiology: respiration,

digestion, etc. By Descartes' time, a growing confidence in the

explanatory power of mechanistic notions allowed him to apportion

even these functions to the machine-like body, effecting a radical

split between the intellect and the gross material world of the

flesh. In his account, Descartes helped himself to a little

understood gland hanging from the base of the brain, the pineal,

whose role in the body was not understood at that time. The

pineal, which lies on the mid-line of the head, between the third

and fourth ventricles, appealed partly because it was a singular

entity, and not doubled on the right and left, as are all brain

structures. In somewhat convoluted fashion, Descartes appealed to

this structure to underwrite the interaction of the soul and body,

an attempt that he never completed to either his satisfaction or

that of others.

These metaphysical issues are very well known, and are regurgitated at length in any introductory material on the philosophy of mind. Descartes' failure to complete his metaphysical project might suggest that his approach would be superceded, and would wither on the vine as scientific accounts of both physiology and psychology came to be constructed on surer empirical and theoretical grounds. Yet this has not happened. Even the most ardent critics of such a division between intellect and body struggle to free themselves from the more intransigent idea that one exists in separation from the world. The fact that we can still use terms such as "the external world" and "my inner thoughts" shows that Descartes' starting point, if not his final terminus, still represents some kind of default assumption, a conviction, or faith, that we have not let go. The unspoken metaphysics of everyday understanding, of common sense, is still one in which the qualitative aspects of reality are divorced from the three dimensional geometry of volumetric space, augmented by the unfolding of this picture through the fourth dimension of time.

Here, we must acknowledge that Descartes is frequently, almost conventionally, held to account for a fundamental stance with respect to the self that he did not invent nor explain, but that must be seen as arising over a much larger period of time, and under many contributing cultural influences. Descartes, in his famous Second Meditation merely gives this voice when he exclaims, from a position of absolute certainty, "Je suis! J'existe!" Such is the hold that the newly modern view of isometric space had on Descartes, and still has on us, that his assertion seemed necessary, for the material world threatened to assert itself over the indubitable qualitative reality of a living subject. To reiterate: the view that reality is four-dimensional, and geometric, is a questionable metaphysical postulate that underlies most of our common-sensical thinking about reality. To work, it requires the separation of the qualitative (experienced) from the quantitative (measured), which leaves us with nowhere for our lived reality.

It is not my goal here to attempt to provide a superior metaphysical account, but rather to show how the projective image, inscribed (or as-if inscribed) in a quasi-mechanical manner from a determinate point in three dimensional space, has come to further shore up the received radical separation of mind and matter. Just as the acheiropoieton offers the icon worshipper an assurance of veracity which anchors the cascade of subsequent copies, and thereby allows the believer access to the divine source, so the projective image, coming into being first with the development of linear perspective, but given an overwhelming boost through the development of photography, came to promise the materialist, for whom Euclidean isometric space is the bedrock of existence, a uniquely privileged representation of reality. Irrespective of how the image was actually produced, whether through film exposure or through skillful painting, the representation of things from a static point in 3-dimensional space conveyed a sense of fidelity to material things, to the layout of surfaces and their illuminations, that seemed to be objective, and hence real, in a way that a freely composed image could never be.

There was a brief period in the Twentieth Century when the fond notion that "the camera cannot lie" appeared somewhat plausible. The mechanical mode of generation seemed to ensure fidelity to the facts of the matter, and the unprecedented level of detail available in a photographic image seemed to provide a bulwark against the designs of the forger. With analogue film, it was very difficult to engineer something that appeared to be a photograph, but wasn't. That didn't last terribly long, however, and at the latest with the advent of Photoshop and CGI, it became clear that the mere appearance of photographic realism was not a guarantee of documentary purity. But the projective image was considerably older than the photograph, and the loss of certainty that has arisen has by no means reduced the exposure of anybody to projective images.

Media matter. My concern in this short essay is with images of a specific type, and the manner in which they continually underpin a specific view of reality that is, in its own way, just another image, another constructed representation of reality, which we frequently treat as if it were reality itself. We are now an image saturated culture. Images, along with texts, are, for most of us, the principal means by which we find out about the world, interpret, imagine, and document it. And this is not only our recent history, it is our future too, as the images and texts proliferate and threaten to overwhelm us.