The Projective Image as Materialist Icon

How photographs reinforce materialist articles of faith, and how livestreams may act as interpersonal portals

This document is meant to be read on a full sized screen. If reading on a phone, the reader may have to tap the ⊕ icon to reveal illustrations and margin notes.

Table of Contents

- 1. Veronica, The Patron Saint of Photography

- 2. Space, Time, and the Projective Image

- 3. The Livestream as Portal

1. Veronica, The Patron Saint of Photography

Fig. 1: Veronica and her veil,

by El Greco. (Image credit)

As he toiled up the Hill of Calvary, sweating and bleeding

profusely, Jesus was met by a woman named Veronica who mopped his

face with her veil. The veil, it is said, came away with an

imprint of Christ's face on it. The event is celebrated in

innumerable Western Christian churches as the sixth of the

fourteen Stations of the Cross. This image was formed by direct

contact with the original, more in the manner of a brass rubbing

than a photograph. An image created in this manner arises from

direct contact with the original, and as a result, it has an aura

of unfalsifiability about it. It would certainly be admissable as

evidence in a criminal trial. For this reason, Veronica is known

as the patron saint of photography (and also of laundry, though

that need not concern us further).

Fig. 1: Veronica and her veil,

by El Greco. (Image credit)

As he toiled up the Hill of Calvary, sweating and bleeding

profusely, Jesus was met by a woman named Veronica who mopped his

face with her veil. The veil, it is said, came away with an

imprint of Christ's face on it. The event is celebrated in

innumerable Western Christian churches as the sixth of the

fourteen Stations of the Cross. This image was formed by direct

contact with the original, more in the manner of a brass rubbing

than a photograph. An image created in this manner arises from

direct contact with the original, and as a result, it has an aura

of unfalsifiability about it. It would certainly be admissable as

evidence in a criminal trial. For this reason, Veronica is known

as the patron saint of photography (and also of laundry, though

that need not concern us further).

Images made by direct transfer, without free invention, are known as acheiropoieta, or "things not made by hand." Such images bear a very direct relation to their source, and they have, accordingly, been especially venerated within image-making traditions in which fidelity to an original source is highly valued. The Shroud of Turin is another such acheiropoieton. The famed Mandylion of Edessa is another. In each case, the representation of the original on the cloth or canvas is not a free invention. It arises causally, through contact, one surface to another. For worshippers of such images, it may afford a way to directly access the source—and this privileged relation between representation and reality may merit our attention too as we consider other paths from representation to reality.

Fig. 2: King Abgar

receives the mandylion of Edessa. Anonymous picture from

St. Catherine's Monasery, Egypt. (Image credit)

Nobody is quite sure what happened to the Veil of Veronica. A

piece of cloth that may or may not be the original veil may or may

not be housed in the Vatican. But there are several images that

claim to be direct copies of the original veil. They were produced

in a different fashion, by manual copying rather than contact and

imprint; but the fact that the copying was done in the presence of

the original matters greatly for icon worshippers. The Veil of

Veronica is thus one source for a rich tradition of icon

production, in which each successive icon is copied from a

preceding model, in (presumed) unbroken succession back to the

original. The original, here, might be taken to mean Christ's

face, rather than the Veil.

Fig. 2: King Abgar

receives the mandylion of Edessa. Anonymous picture from

St. Catherine's Monasery, Egypt. (Image credit)

Nobody is quite sure what happened to the Veil of Veronica. A

piece of cloth that may or may not be the original veil may or may

not be housed in the Vatican. But there are several images that

claim to be direct copies of the original veil. They were produced

in a different fashion, by manual copying rather than contact and

imprint; but the fact that the copying was done in the presence of

the original matters greatly for icon worshippers. The Veil of

Veronica is thus one source for a rich tradition of icon

production, in which each successive icon is copied from a

preceding model, in (presumed) unbroken succession back to the

original. The original, here, might be taken to mean Christ's

face, rather than the Veil.

There are very few originals that have come into being in this quasi-miraculous fashion. The shroud of Turin is displayed only a few times in each century. The Veil and the Mandylion may be presumed missing, if they ever existed. A haze of incredulity will always accompany any physical object for which such a genesis is asserted. The scrutiny visited upon the Shroud of Turin is probably unparalleled in its intensity, despite the obvious difficulty in establishing truths related to objects with such long and contested histories. Most icon sequences start instead with a portrait of the subject done from life, which may then give rise to cascades of copies, each extending the unbroken line from the source. The most famous such sequence stems from a portrait or portraits of the Virgin Mary reputedly (if implausibly) painted by the evangelist, Luke.

The icon traditions of the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christian churches go back to the early centuries of Christianity, and though now secure, they have been the source of substantial controversy, most notably during the Byzantine iconoclasm of the 8th Century CE. In this period, iconoclasts accused iconophiles of directing their pious attentions to dead objects, unworthy of veneration. The iconophiles countered that icons were anything but the lifeless objects their accusers described, but were, by virtue of lying within a continuous unbroken chain of succession, an appropriate means of retaining meaningful contact with their original sources. The debate was long, rich, and ended with the restoration of the practice of icon veneration.

Iconoclasm was nothing new, even in the 8th Century. More than two thousand years before that, the oddball pharaoh Akhenaten, father of the more famous Tutankhamun, had erased the names of Amun and Mut from monuments, temples, and documents, thereby depriving those older gods of direct contact with his people. In 2017, the United States of America is witnessing widespread anger directed towards momuments erected in the 1920's and valorising Confederate figures. The arguments about the relation of the present bronze statues to events and persons of the past is once more a heated topic.

Iconoclastic wars and outbursts keep recurring. There is clearly something at stake here that resists rational deliberation and a reasoned solution. At the heart of the matter is the relation between an image and "reality," where the latter term must be seen as a locus of perennial contestation. When the images in question depict gods or generals, it is clear that there are larger, and more political, issues at stake than mere facts. When iconoclasts and iconophiles debate the suitability of an icon for veneration, they are wrangling about the path one might trace from the present icon to some past original state of affairs. Iconophiles insist that the path is traversable, such that at every stage, as we walk back from the present icon, through the succession of copies, each step is protected by the mores and tradition of icon production, ensuring that no flight of fancy corrupts the original, no creative extrapolation intrudes in the careful preservation of this unbroken chain. Iconoclasts counter with claims that an artefact is being mistaken for a (presumed) original, a representation for its (claimed) source, an image for its (supposed) model.

Fig. 3: Extreme trompe

l'oeil effect in an anamorphic image. Also shown is the ideal viewing

point for the image, from which the most startling photographs can be

taken. (Image credit)

The confusion of a representation with its model is a common

enough occurrance. A rather obvious example arises when a viewer

is fooled by the three-dimensional appearance of a trompe l'oeil

picture such as that shown here. This particular example

exemplifies the genre of anamorphic street art, typically done

with chalk. Such images are meticulously crafted so that they

appear compelling, even frightening, when viewed from one specific

location in three dimensional space. Furthermore, the effect

requires that the viewer close one eye, and remain completely

still. The illustration here (Fig. 3) shows not only the image,

but the manner in which the artist has signalled the optimal

viewing point, by providing a static metal ring. This manner of

viewing, from a single point and without movement, may briefly

induce the illusion that one is in the indisputable presence of

the things depicted, here a gaping icy chasm. The illusion is

short-lived, for the viewer will move, and they will open that

other eye, and with that, the illusion is punctured and

deflates. A great deal of the pleasure to be had by viewing such

scenes is the knowing tension between the brief but compelling

illusion, and the background knowledge that it is, indeed, nothing

more. A photograph of such an anamorphic drawing has the

paradoxical effect of making it seem to the viewer of the

photograph, that were she present at the place from which the

photograph was taken, the effect might be utterly convincing,

which is interestingly unlike the experience of actually being

in the presence of the tromp l'oeil image itself.

Fig. 3: Extreme trompe

l'oeil effect in an anamorphic image. Also shown is the ideal viewing

point for the image, from which the most startling photographs can be

taken. (Image credit)

The confusion of a representation with its model is a common

enough occurrance. A rather obvious example arises when a viewer

is fooled by the three-dimensional appearance of a trompe l'oeil

picture such as that shown here. This particular example

exemplifies the genre of anamorphic street art, typically done

with chalk. Such images are meticulously crafted so that they

appear compelling, even frightening, when viewed from one specific

location in three dimensional space. Furthermore, the effect

requires that the viewer close one eye, and remain completely

still. The illustration here (Fig. 3) shows not only the image,

but the manner in which the artist has signalled the optimal

viewing point, by providing a static metal ring. This manner of

viewing, from a single point and without movement, may briefly

induce the illusion that one is in the indisputable presence of

the things depicted, here a gaping icy chasm. The illusion is

short-lived, for the viewer will move, and they will open that

other eye, and with that, the illusion is punctured and

deflates. A great deal of the pleasure to be had by viewing such

scenes is the knowing tension between the brief but compelling

illusion, and the background knowledge that it is, indeed, nothing

more. A photograph of such an anamorphic drawing has the

paradoxical effect of making it seem to the viewer of the

photograph, that were she present at the place from which the

photograph was taken, the effect might be utterly convincing,

which is interestingly unlike the experience of actually being

in the presence of the tromp l'oeil image itself.

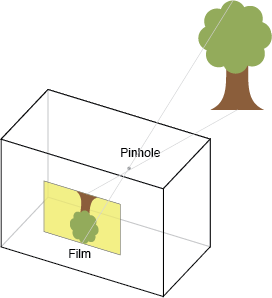

Fig. 4: Geometry of the

projection of an image within an idealised pinhole

camera. (Image credit).

The optimal viewing point for an anamorphic drawing like the

above plays a role that is much like the hole in an idealised

pinhole camera through which an inverted image is projected onto

a surface. While the geometry of optical projection

through non-idealised camera lenses and eyeballs is much more

complex than this simple schema, being importantly modulated by

the material and geometric properties of the lens, this

arrangement is more or less what most of us have in mind when we

think of the quasi-mechanical capture of an image by a stationary

camera of any sort. It provides a simple way of thinking about how

an image is formed on the retina in the back of the eye, or how a

dewdrop on the grass in the morning may appear to contain a

projected image of the garden. The relation between the image so

cast, and its source, seems to us to be mechanical, based solely

on the geometrical properties of light and space. It is presumably

for this reason that Veronica, who likewise captured an image

directly, without stylistic embellishment or artistic

intervention, has come to be so closely associated with

photography.

Fig. 4: Geometry of the

projection of an image within an idealised pinhole

camera. (Image credit).

The optimal viewing point for an anamorphic drawing like the

above plays a role that is much like the hole in an idealised

pinhole camera through which an inverted image is projected onto

a surface. While the geometry of optical projection

through non-idealised camera lenses and eyeballs is much more

complex than this simple schema, being importantly modulated by

the material and geometric properties of the lens, this

arrangement is more or less what most of us have in mind when we

think of the quasi-mechanical capture of an image by a stationary

camera of any sort. It provides a simple way of thinking about how

an image is formed on the retina in the back of the eye, or how a

dewdrop on the grass in the morning may appear to contain a

projected image of the garden. The relation between the image so

cast, and its source, seems to us to be mechanical, based solely

on the geometrical properties of light and space. It is presumably

for this reason that Veronica, who likewise captured an image

directly, without stylistic embellishment or artistic

intervention, has come to be so closely associated with

photography.

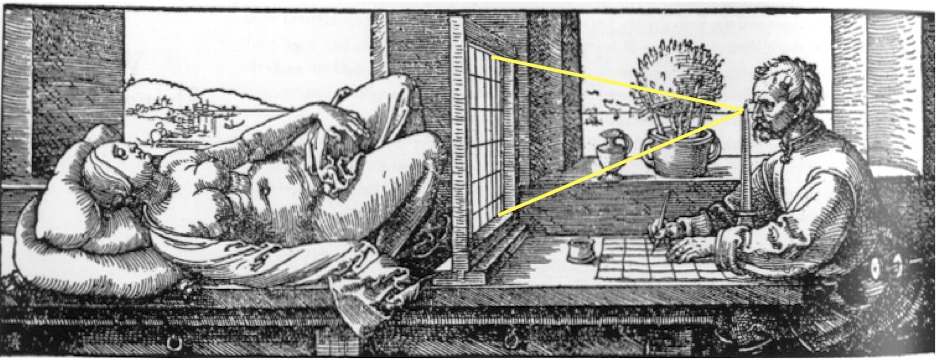

Fig. 5: Projective geometry

used in the creation of an image conforming to the

conventions of linear perspective. (Image credit).

Images created as if in this idealised manner may be considered as

a class, including paintings and drawings done using linear

perspective (see Fig. 5), anamorphic street art, and of course the

still photograph. I will call all of these projective images,

because I am not aware of a term of art that groups such images

together. For now, I will exclude moving images captured in a

similar manner, but we will have to return to the topic of

movement in such images shortly. Each projective image has an

associated optical centre. In the case of a painting or

drawing, this is the point at which the artist may be thought to

place their single open eye while viewing the scene in front of

them. For images generated by actual projection, it is the point

at which the rays drawn from the world towards the projective

surface cross (ignoring the complexity introduced by the physics

of both lenses and screens).

Fig. 5: Projective geometry

used in the creation of an image conforming to the

conventions of linear perspective. (Image credit).

Images created as if in this idealised manner may be considered as

a class, including paintings and drawings done using linear

perspective (see Fig. 5), anamorphic street art, and of course the

still photograph. I will call all of these projective images,

because I am not aware of a term of art that groups such images

together. For now, I will exclude moving images captured in a

similar manner, but we will have to return to the topic of

movement in such images shortly. Each projective image has an

associated optical centre. In the case of a painting or

drawing, this is the point at which the artist may be thought to

place their single open eye while viewing the scene in front of

them. For images generated by actual projection, it is the point

at which the rays drawn from the world towards the projective

surface cross (ignoring the complexity introduced by the physics

of both lenses and screens).

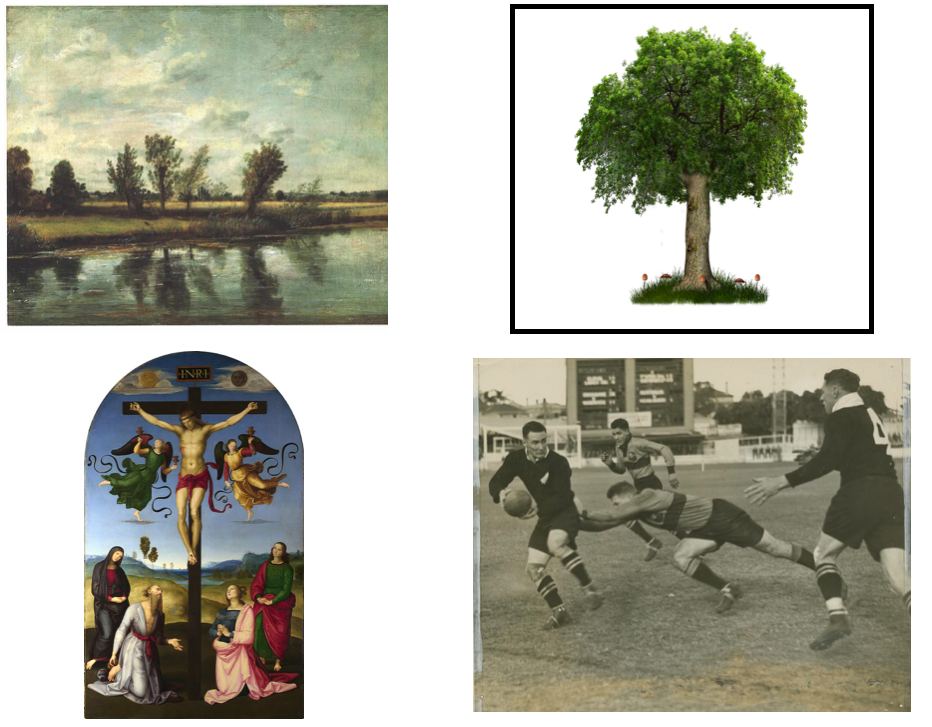

In the above panel, four images are displayed that illustrate some features that serve to distinguish projective images from others. It is not to be expected that images will always be neatly categorisable in this manner. Starting at the top left, we see a landscape by Constable (Water meadows at Salisbury, 1820). This is clearly an image painted from a determinate spot, at a specific time of day. Although a painting, rather than a photograph, Constable has provided a wealth of incidental detail specific to time and place to anchor this image. It does not take a stretch of imagination to imagine the same location viewed from the same spot a few minutes earlier or later, so that this painting, which took many hours to make, seems tied to an instant. This is a projective image.

At top right we see a tree, rendered photorealistically, together with a little clump of ground. But the tree is free floating, not tethered to any specific time or place. This tree has no history and cannot be found on any map. Even if there were an actual tree that served as model, this image does not preserve its spatio-temporal embedding. Despite the photographic detail, this is not a projective image.

At bottom left we have a crucifiction by Raphael. This painting is dated 1502/3, and so the painter has at his disposal the techniques of linear perspective. There is a landscape in the background in which distant objects are rendered at smaller sizes, but overall the painter has not enforced a realistic relation of pictorial elements to a three dimensional space. The angels on either side of the Christ figure are smaller than any of the human figures for reasons that have nothing to do with space and time. So the image is not projective.

Finally, on the bottom right, we have a still photograph taken from a game of rugby. Time has been frozen. The figures are suspended forever in this one instant, and it requires no effort to recognize that the events portrayed are continuous, extending before and after the moment of exposure. This is clearly a projective image.

We live in an image saturated culture, and many of those images are projective images. Such images have provided us with a powerful metaphor for understanding the relation between one who sees, and the world that is seen in this manner. That this way of understanding an image involves a metaphor may not be obvious. Indeed, the purpose of the present document is to lay out the claim that it is, in fact, a metaphor, and that the relation of such images to what we might call "reality" is not straightforward, not mechanical, and not objective in any simple sense. Projective images, I will suggest, have become icons, through which we feel that we access an underlying reality in a particularly important way. Much like the acheiropoieton, we interpret such images as if they arose by direct transfer or contact, without embellishment or addition. But as with icons, this presumed relationship relies on a great deal of faith and tradition. In particular, it leans heavily on a view of reality as material and thus volumetric, and of mind as separate from nature. In the 21st Century, neither of these may be asserted as simple truths, and we may stand to learn something important by asking how, and why, projective images came to exert this power.