Auditory Events

Our phenomenal worlds are full of events. A car beeps outside, an itch intrudes, there is a knock at the door.... In describing such happenings, we naturally parse the world into discrete events. We use vision and audition together, but many events only make themselves known to us through sound. Events are intrinsically temporal, and, among our sensory modalities, audition is uniquely temporal in nature.

We here consider events of sufficiently short duration to fall into what some have called the "psychological present", that is, the half-second to one second time span (the boundaries are fuzzy) within which something is immediately experienced, rather than inferred. Consider, if you will, the difference between observing movement of the second hand on the clock and movement of the hour hand. The former moves within the psychological present, and is directly experienced. The latter can also be deduced to have moved, but its motion is too slow to register in immediate experience.

One question to be asked of such events is whether they can be grouped into event types, and on what basis this might be done. It seems a priori unlikely that a clear partitioning of naturally occurring sound events into discrete types would succeed. Nevertheless, it may be possible to identify prototypical event types which occur with some frequency in any natural environment.

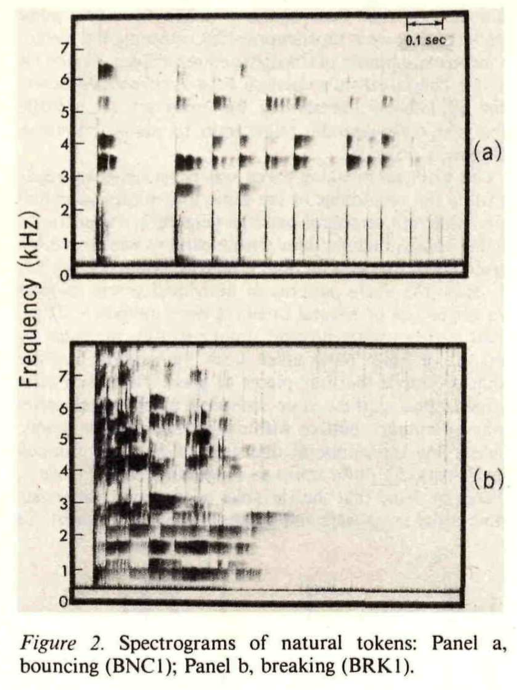

The study of naturally occurring sound types and their significance for a listening organism is the topic of the nascent field of ecological acoustics. In one seminal study (Warren and Verbrugge, 1984), researchers identified breaking and bouncing events as classes, and investigated their spectro-temporal properties. What they found comes as no surprise if we consider the nature of these two kinds of events. When something breaks, there is an initial, brief loud sound, followed by the sounds of multiple pieces (each breaking or bouncing in turn) which are uncoordinated in time. When something bounces, there is an initial impact, followed by a series of impacts whose intensity and temporal spacing decreases exponentially. These properties hold, regardless of whether the object breaking or bouncing is made of glass, clay, metal, etc. That is, there is an acoustic structure to both breaking and bouncing events that is specific to the event type, and is essentially independent of the material constitution of the object being mistreated.

The above image (from Warren and Verbrugge, 1984) shows spectrograms of naturally occurring breaking and bouncing events. In each case, there is a percussive element of high intensity, followed by a lower intensity sequence of events. These have very different temporal structures for the two event classes: in the breaking event (lower panel), numerous shards impact, some of them breaking further, some bouncing or coming to rest, with no temporal coordination among them. In a bounce (top panel), there is a single series of subsequent impacts with temporal spacing and intensity decreasing over time.

The structure of these two event classes differ, but they have something in common. Each starts with a single loud percussive event of high intensity, followed by a diminishing series of further events. We might describe their common structure as a "head", and a "tail", with the difference between the event classes lying in the structure of the tail. This reading of the two event classes suggests that we might attempt a rough taxonomy of single event types, and their combination into two-part events (or more), to see if we can recognize other familiar types of auditory event.

It should come as no surprise that two or more sounds may be perceived as belonging to a single event. Well known illustrations of this include the fusion of conflicting auditory and visual cues, in for example the Mc Gurk Effec, or in the induced perception of a double flash when two rapid beeps are played. Cue conflicts are relatively rare. We are here concerned with the perception of a single event, in the presence of two distinct sounds.

Single Event Types

To a first approximation, we can categorize sustained sounds roughly as shown below. Examples are give of each category, though no pretence is made that these categories have clean boundaries. Sustained sounds may, of course, be arbitrarily long, but we will consider such sounds in as far as they may be experienced within the psychological present, and especially, in as much as they may partake in composite sound events. Clearly, sustained sounds are no rariety in our environment, and not a whole lot is achieved with this initial classification.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Punctate | Sustained, continuous | Sustained, irregular | Sustained, periodic | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

Composite Sound Events

Things get more interesting when we turn to composite sound events. Initialy, we will consider only those consisting of two of the above types. It is not difficult to see both the bouncing and breaking events as composites of a punctate event and either a sustained regular or a sustained irregular event, respectively. However, the regular impact events of the bouncing event are further modulated by an exponential decrease in inter-onset interval timing and intensity. The same is true of the bouncing event, as each shard generates its own breaking-or-bouncing mini-event, but the overall temporal structure is, of course, irregular.

We might thus caricature the two event types above in this fashion:

|

|

| Bouncing event | Breaking event |

Interestingly, it is not difficult to find other clear events with a similar structure. In the following examples, the initial strong event is a cause, and the subsequent sustained event is an effect which exhibits a reduction in intensity (and perhaps temporal interval spacing, and perhaps frequency). In each case, the tail is a continuous sustained sound with decaying intensity.

| Lighting match: | Thunder: | Door opening: |

It is not dificult to imagine similar events: a branch breaks from a tree with a crack followed by a decaying tearing sound; A rock falls and dislodges some smaller rocks below, etc. Perhaps we can push this a little further, and consider the mirror image of the above prototypical acoustic event structure: a gradual increasing lead terminated by an abrupt punctate sound. Again, examples are not hard to find.

| Door closing: | Skid and crash: | Drawer closing: |

The above examples all have similar macroscopic temporal structure: a lead in, followed by a percussive or punctate event. We can caricature this as illustrated in the following two synthetic examples:

| Ramp up and crash | Crash and ramp down: |

These observations lead to some interesting suggestions for future work. It has long been known that simple visual displays can induce a sense of causality in the viewer, as when a single disk enters a frame, travels as far as a second disk, and stops, at which time the second disk begins moving in the same direction. This simple cartoon is perceived as a collision event, in which the momentum of the first disk is passed to the second. Albert Michotte introduced the study of perceived causality in his 1945 book "Perception of Causality". For the most part, subsequent work has focussed on vision, and has been complicated by a body of work on perceived animacy (as when an animated circle appears to chase an animated square, which in turn appears to undertake evasive action). The question of what structure a group of sounds need to have to be perceived as stemming from a single event has not et been adequately addressed. Work on audition, based mainly on the pioneering work of Albert Bregman, has looked at the parsing of the mixture of sounds reaching the ear into distinct sources. However, in a causal event, the participating sounds may, in fact stem from different sources, yet be perceived as causally related (imagine the clack of the tensely anticipated golf putt, followed by the sigh of the attentive crowd as the ball misses the hole).

Work on ecological acoustics has developed in several directions, including the perception of material properties (telling metal from glass, for example) and has often tried to address themes which have been productive in the study of vision (acoustic tau, specifing time to contact). Little has been done to characterize statistically prevalent event types in acoustics, beyond the groundbreaking study of breaking and bouncing events mentioned above. The above conisderations suggest that there is much more to uncover here in schematizing the properties of events and their associated sounds.

Finally, it is tempting to look ahead and to wonder what such work might tell us about more complex uses of sound. In particular, is it not possible that certain event types we are familiar with may have been exploited by speech systems, facilitating word recognition? The intensity profile of a maximally unmarked syllable such as /ta/ bears striking resemblance to the events sketched above. The iambs and trochees of English rhythm are certainly suggestive of two-part events with a strong and a weak element in each, much as outlined above. Likewise, the most unmarked intonation contour found in English (often described technicaly as H L-L%) has a structure not dissimilar to the dynamics sketched above. Might an understanding of event structure in sound help us to move forward in our study of speech and music?

Had enough? Then sit back and wonder at some simple audio-visual event trickery.