Genitum, Non Factum

Thoughts on a Biological Turing Test

Page 2 of 3

Table of Contents

Life Itself

There is an alternative tack to take, that has been developed over several decades now Varela, F. J., Thompson, E. & Rosch, E.(1991) The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press. . Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in Life. Harvard University Press. Much like my stated goal of trying to distinguish in principle between an artifact and a living being, it tries to understand the nature of living systems, without leaning upon a long, tentative, incomplete laundry list of properties that might or might not belong together (metabolism, reproduction, growth, and the spectacularly poorly defined "functional activity"). Instead it treats of life as a phenomenon that must be taken on its own terms, and in framing its discussions, it typically leans heavily upon a stylised description of the form of organisation found in a single cell. We will meet that description in a little bit.

At the centre of this view of life is the recognition that living beings strive in the service of their own goals. They only make sense if you see them as inherently teleological. Aristotle might find this familiar territory! Kant was puzzled by the fact that living organisms seemed to have goals, to require explanation in terms of "functions," and to generally act as agents. The activity of any living being, whether it is the pulsing of a jellyfish or the planting of crops by a far-sighted farmer, makes sense only when we recognize that it produces effects conducive to the further existence of the organism. Jellyfish and farmers and all life forms are of this nature. Their actions make sense only if we interpret them from the perspective of the agent itself. Kant struggled, and failed, to accommodate this within his view of a deterministic, mechanical universe Weber, A., & Varela, F. J. (2002). Life after Kant: Natural purposes and the autopoietic foundations of biological individuality. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 1(2), 97-125. .

Space precludes any kind of proper account of the Mind and Life, or Enactive approach, within which these ideas have been curated. (I use these two terms interchangably, but do not suggest that they have precise boundaries, or admit of any kind of ideological consensus. Others draw distinctions there, and the arguments must be seen as ongoing, rather than settled.) Its radical starting point is the idea that the subjective point of view, however we understand that, is not something produced by nervous systems, or taking place within skulls. The singular perspective of the living being is given primacy, and is interpreted as arising from the densely networked processes that together constitute life itself. Rather than attempt to describe this approach in detail, I'll just place some references here and move right along. Stewart, J. R., Gapenne, O., & Di Paolo, E. A. (2010). Enaction: Toward a new paradigm for cognitive science. MIT Press. Froese, T., & Di Paolo, E. A. (2011). The enactive approach: Theoretical sketches from cell to society. Pragmatics & Cognition, 19(1), 1-36. If you are not at all familiar with the enactive framework, you'll be taking some things on trust for a bit. But no worries. We will return to these topics on the next page, when we are in need of a new vocabulary for framing scientific questions. [Table of Contents]

Movement, Behaviour, and Goals

Movement just happens. Behaviour has goals. Let us instead return to the tumblebot and Mr Sparkles, and consider how we might understand their actions. Remember, we are looking for fundamental characteristics, not merely contingent detail, so that we could, in principle, distinguish between a living organism and a machine. In each case, I am confident we would agree that we observe movement. One might then ask whether we are looking at behaviour, and that introduces a useful distinction we could make. Movement describes change of position. It is a simple notion. We see movement in both animate and inanimate systems, in the motions of the planets, the violence of an avalanche, and the wiggle of a goldfish's tail. Behaviour is a special way to interpret movement, in which the movement seems to serve one goal or another. So if you see me scratching myself, your understanding is based on your simultaneous recognition of the itch. Scratching is a behaviour. If I happened, by chance, to make the same twitching movement during a Grand Mal epilleptic attack, you would not make the same inference. There you would see the same movement, but you would interpret it differently. So the manner in which we describe something as behaviour will depend upon the goals or purposes we perceive, or suspect.

We are exquisitely sensitive to goals. We might cautiously say

that we see them directly.

If we are shown a bunch of moving points which reenact the

coordinated movement of a person, we see through the dots to the

person and their goal immediately. Instead of moving points, we

see someone kicking, punching, throwing. Careful though! We, as

observers, have now become complicit in the description.

Describing the movement of the planets is not like describing the

movement of a person. Planets exhibit no goals. People appear to.

The interpretation of movement as behaviour, possible for people,

not for planets, hinges on the perception of goals. With this in

mind, if we now interpret the movement of our two selected

systems, the tumblebot and the goldfish, as behaviour, what do we

see?

If we are shown a bunch of moving points which reenact the

coordinated movement of a person, we see through the dots to the

person and their goal immediately. Instead of moving points, we

see someone kicking, punching, throwing. Careful though! We, as

observers, have now become complicit in the description.

Describing the movement of the planets is not like describing the

movement of a person. Planets exhibit no goals. People appear to.

The interpretation of movement as behaviour, possible for people,

not for planets, hinges on the perception of goals. With this in

mind, if we now interpret the movement of our two selected

systems, the tumblebot and the goldfish, as behaviour, what do we

see?

As ever, we need to approach this with some circumspection and care. We are discussing a specific example, and in this specific case, we actually know quite a lot about goals. In the more general case, however, things are not so simple. In our exemplary case, both systems display behaviour of some sort. The fish's activity is just the kind of behaviour necessary for a living being to continue living its life. If it stops swimming, eating, excreting, it will die. Like the big, familiar living systems that we usually conjure up when we think of the natural world, This seems to be roughly how we think of the actions of big, well-individuated organisms, such as dogs, humans, even ants. But as we move further afield, and consider algae, corals, lichens, bacteria, our ability to interpret what we see in such purposive terms seems to dwindle. we might best describe its "goings on" as behaviour and not as mere movement, and the goals we observe admit of interpretation with respect to the continued viability of the organism.

But the tumblebot also appears to behave, and not merely to move. It has been engineered to do so. There was willful intent in crafting a smooth sphere well matched to the friction characteristics of floors and floor coverings, in placing a small overbalanced motor inside arranged to spin around a central axis, in fashioning a holder for a battery, which, when supplied, provides the necessary energy source. The result is amusing precisely because the actions of the toy appear agentive in its own right. That is, we seem to see behaviour of the tumblebot, but of course we know that the apparent goals are a bit of a trick. There is purpose, but is is the engineer's purpose that underlies the toy, not the intrinsic purposes of the living.

Goal-directedness alone will not suffice for our purposes. But this seems to bring us back to square one. We have two systems, each displaying apparently agentive behaviour, and in order to distinguish between them, we have to refer to a notional engineer who is not present. Both exhibit goal directed behaviour (as all behaviour is goal directed), but they differ in the origin of those goals, which we cannot directly see. There doesn't seem to be any surface feature of the tumblebot that we can point to that is different in kind from the processes subserving the apparent behaviour of Mr Sparkles. What progress have we made?

In parsing a continuous flux of movement into descriptions of behaviour, something very important has just happened: the observer has become entangled in the description of the observed. Goals are not free entities, existing out there in space somewhere. When I perceive a goal, this says something about the relation that obtains between me and that which I am looking at. This point will be crucial as the discussion progresses: a description of behaviour, understood as movement that is goal-oriented, or that serves one or other function, implicates the observer in the observed. Any description of function implicates the observer in the observed.

After that rather strong statement, let us indulge in a small interlude, in which we consider what it is to copy something. [Table of Contents]

Copies and Presence

I had a key cut this morning. The machine used was much like

that illustrated here.

A key cutting machine.

It works by taking an original key, clamping it into position in

the left of the two blocks, clamping a blank in the right block,

and then running a sensor over the original that regulates the

position of the circular grinder, thereby transferring the bumps

and notches of the original to the new key. There is now a

special link between the two keys, and they will, if all went

well, work in much the same way. If you are in a fanciful mood,

you could reasonably say the power to open my door has been

transferred to the blank, without being stripped from the

original.

A key cutting machine.

It works by taking an original key, clamping it into position in

the left of the two blocks, clamping a blank in the right block,

and then running a sensor over the original that regulates the

position of the circular grinder, thereby transferring the bumps

and notches of the original to the new key. There is now a

special link between the two keys, and they will, if all went

well, work in much the same way. If you are in a fanciful mood,

you could reasonably say the power to open my door has been

transferred to the blank, without being stripped from the

original.

Within the tradition of religious icons, a special prominence

is given to images that were not fabricated by hand, but had

instead their origin in the direct impression of the original.

The marks on the Turin Shroud, the Mandylion of Edessa (see picture) or

the Veronica which bore the imprint of Christ's face during his

passion, are examples.

The Mandylion of Edessa.

The technical term acheiropoieton (not made by

hand) is used to distinguish these from what we might call

"mere" fabrications, and these images were granted a seriousness

denied others because of their direct lineage that could be

traced back to a potent original. Copies taken directly from

these images inherited some of the potency of presence.

The Mandylion of Edessa.

The technical term acheiropoieton (not made by

hand) is used to distinguish these from what we might call

"mere" fabrications, and these images were granted a seriousness

denied others because of their direct lineage that could be

traced back to a potent original. Copies taken directly from

these images inherited some of the potency of presence.

A special value has typically been accorded icons originating in the presence of the saint or notable depicted. The evangelist, Luke, has a reputation for having painted the Virgin Mary herself (implausible, as he was born somewhat late for that). But the association with the presence of the Virgin has since ensured a special reverence for icons which are considered to lie in the line of direct copies extending back to an essential original.

In Islamic tradition, the core texts are not just the Koran and the words of the prophet, but also the hadith, which consists of the reported sayings of the followers of the prophet. The details of just what counts as part of the hadith will vary from one variety of Islam to another, but they all have in common the unbroken link from the utterance to the Prophet himself. That is, for any element in the hadith, it must be possible to demonstrate that there is an unbroken chain from the utterer, back to the Prophet himself (the isnad). The Prophet may have uttered the words, or merely indicated a sentiment, but the point of the chain is to maintain the succession of unbroken links that guarantees authenticity within the tradition.

Copying is, of course, at the heart of life itself. Any plausible discussion of the nature of life must acknowledge the huge role of copying, one generation to the next. Copying by splitting, copying by sexual reproduction. What is passed on in this manner? The structures and processes of the body, of course, but something more than that also. We will need to consider the role of copying within living beings to make progress, but first we will need to briefly visit the slightly eccentric Estonian-German aristrocrat-scientist, Jacob Von Uexküll. [Table of Contents]

Umwelt: The world you meet

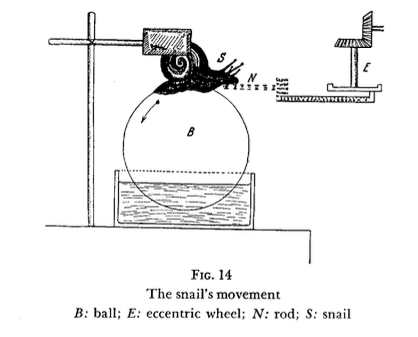

Jacob von Uexküll had an experimental gift. Consider the

strange device illustrated here.

Treadmill for a snail. From Von

Uexküll, J. (1992). "A stroll through the worlds of animals and

men: A picture book of invisible worlds." Semiotica, 89(4),

319-391.

This is a treadmill built for a snail. The large ball

rotates more or less freely, allowing the snail, who is held

firmly in place, to nevertheless crawl. A small rod extends

to beneath the snail's "foot", and it delivers a small regular

series of taps. If the taps occur slowly, the snail clearly

perceives each tap individually, and seeks to get away from

the source of the disturbance. But once they reach a

frequency of 4 times per second, the snail's behaviour

changes. It now appears to perceive the taps as continuous,

and instead of trying to exit, it tries instead to climb onto

what seems to it to be a continuous load-bearing surface. We

experience something similar when we observe a rapidly

flashing light, or hear a repeating click. Below about 20

flashes or clicks per second, we perceive discrete events. At

more rapid rates, we perceive a constant light, or a low

pitched continuous tone.

Treadmill for a snail. From Von

Uexküll, J. (1992). "A stroll through the worlds of animals and

men: A picture book of invisible worlds." Semiotica, 89(4),

319-391.

This is a treadmill built for a snail. The large ball

rotates more or less freely, allowing the snail, who is held

firmly in place, to nevertheless crawl. A small rod extends

to beneath the snail's "foot", and it delivers a small regular

series of taps. If the taps occur slowly, the snail clearly

perceives each tap individually, and seeks to get away from

the source of the disturbance. But once they reach a

frequency of 4 times per second, the snail's behaviour

changes. It now appears to perceive the taps as continuous,

and instead of trying to exit, it tries instead to climb onto

what seems to it to be a continuous load-bearing surface. We

experience something similar when we observe a rapidly

flashing light, or hear a repeating click. Below about 20

flashes or clicks per second, we perceive discrete events. At

more rapid rates, we perceive a constant light, or a low

pitched continuous tone.

Von Uexküll's observations covered animals from the single celled paramecium through the limpet, the tick, the hen, fly, dog, human, and many more. In each case, he was at pains to observe how the world that is encountered by each organism is not an alien, abstract, detached proposition, but rather it is revealed in strokes drawn by the organism's own capacity for making discriminations, and for acting in the world. Imagine you could listen in on the sonic world of a bat. It would make no sense to you. You would hear a bunch of high-pitched shrieks, glides, and whistles that would only confuse you. Yet from observing bats, we can safely say that is not what a bat experiences at all. Rather, this world of sound is the means by which the bat navigates, identifying food, avoiding obstacles, and finding shelter.

For living beings, worlds arise as a function of bodies and histories. The very properties of space and time, those old chestnuts, so beloved of Kant, that seem to precede any empirical encounter with the world, are themselves shaped by the manner in which each organism is hooked into its world. The snail is living at a different timescale from the experimenter. The spatial world of the blind earthworm is simply incomparable to that of a highly visual ape like us. Animals possessed of a vestibular system, the suite of little accelerometers we find in our middle ear, will encounter space in a manner unavailable to animals without. Things that seem to simply be in the world, such as cars, building, cities, equally simply fail to exist for other animals, like ants, ticks, and moles. Earthworms encounter earthworm worlds, humans encounter human worlds. But there too we need to differentiate. Von Uexküll does not fall prey to the assumption that all humans encounter the same world, with the same perceivable properties and offering the same opportunities for action. No, an astronomer, an archeologist, and a lumberjack put down into the same rural location, will see very different things, and will act differently. In the human case, at least, the world we meet is drawn not just in terms of our sensory modalities and our ability to walk, swim, kick, and sit. We see, and we act, with our full capacity for understanding. The world we encounter arises as a function of our embodiment, but also our history, our path in life, the things we learned along the way, the things we learned to avoid and exploit, to desire and fear, the skills we acquired that changed the opportunities for action, and the categories we came to rely on that make things originally distinct appear similar. These do not change us but leave the world unmoved. They change the world we encounter as subjects, as individuals. Von Uexküll coined the term "Umwelt" to describe the world as it arises for a subject, drawn in strokes that originate in the structure and capacity for discrimination and action of that embodied subject. It is a useful term, not to be mis-translated as simply "environment", for earthworms have earthworm umwelts, and Luxembourgers have Luxembourgish umwelts, which are similar to those of Belgians, but not the same. Your Umwelt will be similar in very many respects to mine, and both will be utterly unlike that of Mr Sparkles. Von Uexküll understood the perspectivalism that must be brought to bear to understand the living. [Table of Contents]

Sharing a world

Humans meet human worlds, worms meet worm worlds. What world do we share? If earthworms occupy different worlds than ticks, and dogs encounter different worlds than limpets, do you and I occupy or meet the same world? The venerable empiricist tradition would have it that we are hooked into the worlds through our senses, and because you and I are similarly endowed (though I may be a bit more short-sighted and hard of hearing than you), we therefore start with the same raw material. But this relies on a dramatic and untenable separation of subject from world. My life has been different from your life. It started differently, and every event was unique and served to create a path of becoming that was different in detail, at least, from yours. Every experience affected every subsequent experience, and the world I meet now has been shaped by all of this. The world I meet will accordingly be drawn with different strokes than that which arises for you. Not that "red" is dramatically different for me than for you, but the significance with which the world is laden is individual, with specific solicitations to action, specific threats, specific aesthetic qualities. This view of our encounter with the world does not allow of partition into perception and cognition. We see, hear, feel with our understanding, always.

We can not rely on a simplistic division between subjective and objective. The (outdated, but persistent) kind of scientific reductionism I lamented earlier valorises a single account of a single world, possessed of structure and form, but entirely without meaning or value. This is the simplistic interpretation of the difficult and complex concept of objectivity. It insists on a single agreed account of being, of that which, in some agreed sense, is. To make progress on our project here of underwriting (or not) a distinction between an organism and an artifact, we will need a different vocabulary, a different way of thinking of science, and a different way of treating of experience. We will need to treat the inherent values of the living with some respect, and acknowledge that they do not dilute and vanish in the wash of close analysis, as a reductionist account would have it.

The paradigm of Enaction provides the vocabulary we need here.. To do so we will avail ourselves of the Mind and Life, or Enactive, framework that we briefly mentioned before. It provides us with a kind of perspectival flexibility that allows us to accommodate more than one scale of values in consideration of a phenomenon. It is a deeply biological theory that has its origins in the principled understanding of the organisation of single cells and their relation to their worlds, not unlike a Von Uexküllian account pared back to its minimal necessary structure. And it tries to get by without appeal to the Psychological Subject, or an unseen Mechanical Mind that seems to be presumed by the competing contemporary accounts. The framework is concerned with many issues that need not detain us here (luckily). For further reading, the references provided on this page may be useful. But we will resolutely not adopt one habit that unfortunately pervades this literature: we will not try to chart a way forward by "paying attention to experience", by "phenomenological analysis" or any other dubious practice that suggests that we can see further than others. Rather, taking a hint from Von Uexküll, we will reason from the outside, as it were, without presuming any kind of heightened awareness of the fabric of any experience, yours, mine, a goldfish's or a toy's.